“And now you know” — Harry Choates was The Godfather of Cajun Music (Part 1 of 2)

Published 12:26 am Thursday, June 16, 2022

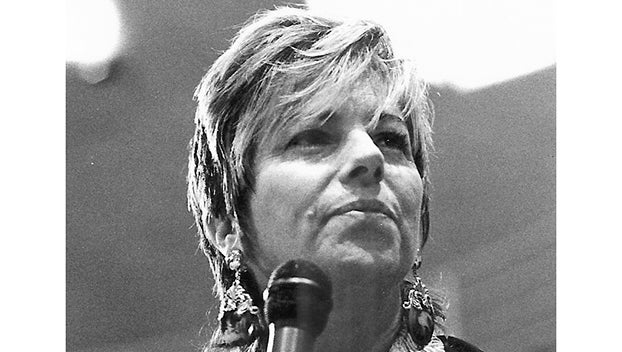

- Harry Choates

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Of all the stars in the field of music that burned out too soon, the most tragic may be Harry Choates.

Choates died in a jail cell in Austin, Texas, after being confined for three days without any alcohol. He went into delirium tremors, or DTs, and began to bang his head on the walls and bars of his cell.

Chronic alcoholism was taking the toll on the 28-year-old musical genius. Three of his friends visited him that last day and saw that he was almost catatonic and was nervously pacing his cell and hitting his head on the wall.

His friend, Jimmy Grabowske, approached a jailer and pleaded with him to try to help Choates, as he appeared to be dying. The guard just shrugged his shoulders and said there was nothing they could do.

The three friends began walking back to the radio station, KTBC, where they and Choates were playing with the Jesse James and his Gang band. Almost to the station, they began to hear the siren of an ambulance. Choates was taken to the hospital and pronounced dead at 2:45 p.m. He died without being seen by a doctor, and the ambulance was called too late.

His head injuries were so severe that rumors of his being beaten to death by the jailers have persisted over the years. Alcohol was constantly in his system, and being deprived of it while in jail probably caused him to go into such a mental state that he caused all the damage himself.

By any definition, Choates was a musical genius. He was born in Cow Island, Louisiana, according to baptismal records or New Iberia, Louisiana, according to his Texas death certificate. No matter it was Vermillion Parish definitely.

About 1930 he moved with his mother to Port Arthur. He was 8 years old and already showing signs of two things, an affinity for music and not wanting to go to school.

The house they lived in was raised on piers and it was easy for the boy to crawl under the house and play there all day instead of going to school. By the time he was 12, he was going to the barbershops and juke joints on Proctor Street.

He saw someone playing a fiddle and decided that he could learn to do that. By merely watching, he was able to learn to make the moves with the bow across the strings and by ear he could learn melodies. He also was developing a flair for showmanship.

He would rise on his toes when he played the high notes. The listeners liked that and began to toss money to him as tips for his playing.

Choates was playing music for money. He liked that and never went back to school. Whiskey was a part of the environment he was in, and he began to develop a taste for that, too. For the rest of his life, the two most important things were his music and his drinking.

In 1940 he began playing with Leo Soileau and Leroy “Happy Fats” Leblanc in their Cajun band. He started playing with a borrowed fiddle. For the rest of his career, he played with borrowed instruments and may never have actually owned his own.

If he did, he would have bought it from a pawn shop and then later sold it to buy something to drink. Choates could play anything with strings and also the piano. Once, when the strings on his bow were broken, he cut them off in a ceiling fan, rosined the wood of the bow and played the fiddle with that.

Choates decided to form his own band, and the Melody Boys organized in 1946. That was also the year he rewrote the Cajun waltz “Jolie Blonde,” and recorded it in Houston on the Gold Star label. Bill Quinn was the owner of the studio and the label. Quinn misspelled the name, and it became “Jole Blon.”

Quinn met resistance getting the song played, but once it began to receive play, it became a hit.

A young Gordon Baxter was beginning his career as a disk jockey at KPAC radio in Port Arthur and liked the song so well the first time he played it that he played it three times in a row. The station manager was not happy, but the listeners loved the song and began to search for it in the record shops.

Boneau’s Record Shop in Port Arthur had trouble keeping it stocked.

(This is the part one of two parts)

“And now you know”

— Written by Mike Louviere